Learning Note: Process and Multitasking

This article is a summary of Chapter 1, section 4-6 of:

Arpaci-Dusseau, R. H., & Arpaci-Dusseau, A. C. (2023). Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces (1.10th ed.). Arpaci-Dusseau Books.

Process: the Abstraction

One key function of an operating system is to virtualize hardware resources. Each program running on the operating system appears to have full control of the CPU. However, in fact, multiple programs running concurrently are sharing the same CPU and are constantly being switched by the operating system. The switch among programs are too fast to be perceptible for humans, creating an illusion that multiple programs are running together.

A process is an abstraction for a running program. The machine state of a process keep track of the resources a process acquires, including the memory used by the process (address space), the values of CPU registers the process is using (most notably, the program counter that indicates which instruction the process should execute next, and the stack pointer and frame pointer that manages the stack used by the process), and sometimes I/O information, such has the files being opened by the program.

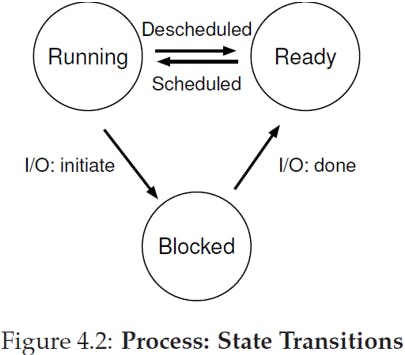

A process primarily has three states (oftentimes there are other intermediate states as well): running, ready, and blocked. Running state indicates that the process is currently occupying the CPU. Ready state means the process is ready to be selected by the operating system to run, but has not been scheduled yet. Blocked state means that the process is performing certain time-consuming operations that make it not ready to run, normally I/O operations such as writing to the disk.

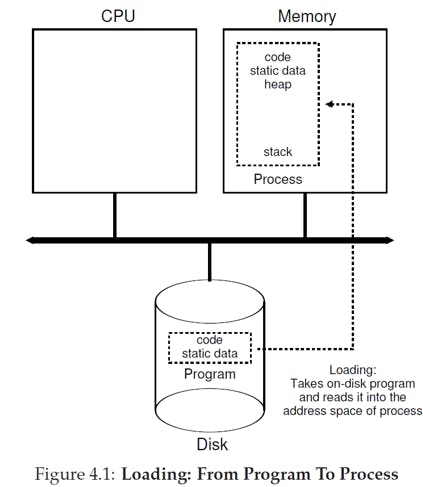

When the operating system needs to start a process, it first load the executable file from disk into the memory. Then, the OS sets up run-time stack and heap for the progress, and conduct other initializations (such as opening file desciptors for Unix). Finally, it jumps into the program entry point, the main() function, and transfer the control of CPU to the process.

Process List (or Process Control Block), is a data structure the operating system uses to keep track of the information of a process. The figure below shows the process list of xv6:

There are a few things to note about the code above. Firstly, the context struct stores the register values of the process when it is being stopped. When the process is scheduled to run again, the register values will be restored for the process to continue running. Secondly, there are other intermediate states besides running, ready, and blocked, including Embryo state where the process is initially created, and Zombie state where the process has exited but yet been cleaned up.

An operating system normally needs to provide the following API for controlling processes:

Creating a new process

Destroying a process

Waiting until a process to exit

Miscellaneous control, such as suspending and resuming process

Getting the process status

In the next section, we will take a closer look of how Unix system implements these API

Interlude: Process API

fork() command creates a child process that is a copy of the parent process. The child process starts right from the instruction where fork() is called, instead of the program entry point.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

printf("hello world (pid:%d)\n", (int)getpid());

int rc = fork();

if (rc < 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "fork failed");

} else if (rc == 0) {

printf("hello, I am child (pid:%d)", (int)getpid());

} else {

printf("hello, I am parent (pid:%d)", (int)getpid());

}

return 0;

}

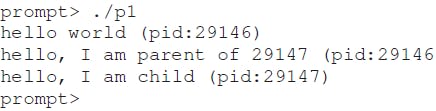

An example output of the program above is as follows (the order for parent and child to print message is indeterminate)

From the output, we can confirm that the child process runs starting from the line (int rc = fork() ) where it is created, since "hello world" is only printed once by the parent process. The function getpid() is used to get the process identifier of a process.

wait() command is used to let the parent process wait until the child process finishes executing, and then continue executing. With wait() command, we can control the execution orders of parent and child process.

exec() command is used to run a different program than the caller process. fork() only allows running a process that is the copy of the program, while exec() is used to run an external program. When exec() is called, instead of creating a new process, the current process is overriden with the instructions of the external program.

The mechanisms of the three system calls may seem odd. However, combining them is useful for implementing the Unix system shell. When the user types in a command to the shell, the shell calls fork() to create a child process to run the command. Then, the child process calls exec() to execute the command. Meanwhile, the shell calls wait() to wait until the child process to finish executing.

Mechanism: Limited Direct Execution

Now that we have learned about details about an individual process, we can take a look at how the operating system runs multiple processes concurrently. The operating system implements time-sharing for multitasking, that is, running a process for a brief amount of time and switching the process running on the CPU. There are two major concerns for implementing multitasking. Firstly, how to ensure the efficiency of running a process, given that the resources it accesses are all virtual abstractions. Secondly, how to make the programs under the control of operating system.

For the first problem, to achieve maximum efficiency, the operating system simply gives up the CPU and allows the process to be run directly on the CPU. This mechanism is known as limited direct execution.

One problem for letting the program directly running on CPU is that oftentimes we want to restrict what the program can do. For example, the program cannot have unlimited access to memory, or perform any I/O operations to the disk. Otherwise, a program may intentionally or accidentally causes damage to other programs or the whole system. To prevent this, user programs are running at user mode, in which the program is restricted in what it can do. The operating system runs at kernel mode, in while it has unlimited access of hardware instructions.

For an user program to perform actions that requires kernel mode priviledge (such as writing to disk), it needs to make system calls to the operating system. During a system call, the user program executes a trap instruction to jump to the OS kernel. The operation system stores the user program's context, including program counter, floa, and register values on the kernel stack, performs the priviledged action, and finally calls return-from-trap instruction and returns to user mode, while restoring the user program context.

The operating system keep tracks of trap handlers for various system calls in a trap table. Setting up a trap table is also a priviledged operation.

The other problem with limited direct execution is how the operating system takes control of the CPU again and switches to another process. Since operating system itself is also a program, it cannot be executed when another program is running on the CPU. Cooperative multitasking is a technique mainly used in early computers, where the user process needs to voluntarily give up CPU for the operating system to take control again. When the program makes a system call or triggers a CPU exception (such as division by zero or accessing a invalid memory address), the operating system can take control of the CPU again and execute process scheduling.

However, there is obvious drawback of cooperative multitasking. If a program occupies the CPU forever (for example, if it has an infinite loop), the operating system will never have an chance to regain the control of CPU and run other processes. In this case, rebooting the system will be the only option. Today's operating systems normally use preemptive multitasking. In preemptive multitasking, a hardware device called timer periodically triggers timer interrupt. At a timer interrupt, the operating system gains control of CPU and can execute process scheduling in the interrupt handler.